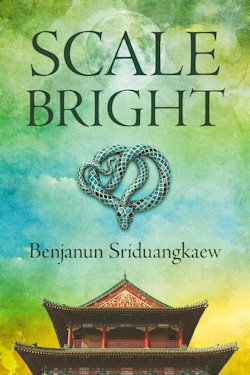

World Fantasy Award winner Lavie Tidhar has it that Benjanun Sriduangkaew may be “the most exciting new voice in speculative fiction today,” and on the basis of Scale-Bright, he might be right. A love story set in heaven and Hong Kong arranged around a troubled young woman’s belated coming of age, it’s the longest and most involved tale Sriduangkaew has told to date, and considered alongside The Sun-Moon Cycle, it represents an achievement without equal.

“An orphan who spent seven years hating equally the parents that died and the extended family that did not,” Julienne, when we join her, lives what you might describe as a quiet life with her adoptive aunts, Hau Ngai and Seung Ngo. The fact that they’re myths in mortal form complicates things a little, admittedly.

Julienne adores them both, though. They’ve given her everything—not least love—and their greatness is an inspiration:

She can’t stop thinking about them. To adore each other so much after so long, for all the complications neither will voice. Julienne hopes that by the time she looks their age she’ll have fixed herself. All her neuroses will be gone, as amusing and harmless as baby pictures. She doesn’t want to think it’s taken Hau Ngai and Seung Ngo centuries to become who they are. They have forever, and she has only a handful of decades. It doesn’t seem right that at twenty-four she still finds herself with problems that should’ve been shed with adolescence, like bad hair and acne.

“To be well, to know confidence, to have someone like Hau Ngai—just a little like, more human and less legend—for her own.” These are her humble hopes. Alas, when your aunts are the archer who shot down the suns and the woman who lives on the moon, all is not so straightforward. So it is that she’s tricked at the outset of the text; swindled by a snake of sorts, who appears to her in the guise of a wounded woman bedecked in an emerald dress:

There is a woman in so extraordinary a colour; there is a woman who bleeds—and no one has noticed. So there must be no woman, or there is no blood.

Her aunts have taught her that Hong Kong is not quite the city she knows. Not half so safe; not half so dull.

Julienne is not naive to the ways of the world—that she casts caution to the wind rather than let this maybe-lady bleed to death is conversely a credit to her character. Next thing she knows, though, a period of time has passed. “She drank your youth,” Hau Ngai explains later. “A few years torn out from the weave of your span. […] What you brought home was malicious; a viper, unless I’ve misread the signs. Reptiles are beguiling.” Still more so than she knows…

It becomes evident, eventually, that the snake needs a favour. Her sister is being held in heaven, and she needs the archer’s assistance to worm her way in. Whether or not she’ll get it essentially depends on Julienne—who, true to form, isn’t sure what to do.

A heady urban fantasy filigreed with the richness of myth, Scale-Bright suffices as a standalone story. Julienne’s journey of discovery—from within and outwith, wonderfully—is begun and done before the thing is finished, giving readers unfamiliar with Sriduangkaew’s fiction a relatively thrilling throughline.

Truth be told, though, the entire exquisite experience of it is apt to be substantially more satisfying if you’ve read the three stories of The Sun-Moon Cycle so far, which is where—aside the viper—this narrative’s characters come from. We met sweet Seung Ngo and the martial archer she married in ‘Woman of the Sun, Woman of the Moon,’ whilst we were introduced to Julienne in ’Chang’e Dashes from the Moon.’ Even Xihe—the mother of the suns Hau Ngai shot out of the skies in ’The Crows Her Dragon’s Gate’—reappears here, albeit briefly.

Characters aren’t the only thing Sriduangkaew’s new novella has in common with said shorts. Its themes—forbidden love, gendered expectations and the need to break free from these—can be found throughout The Sun-Moon Cycle; its several settings take shape in those stories; as does its manifest fascination with mythology. Such a shame that they’re not a part of the package… though they remain freely available.

It’s clear, in any case, that Sriduangkaew’s craft translates to longer form fiction without losing any of its impact. Scale-Bright’s wonderful world boasts delicately drawn characters and an affecting narrative, bolstered on the sentence level by exquisite exposition and deft description. “A laptop tossed into the fountain […] lies parted and silver, an oyster of silicon and circuitry,” and later, relatedly:

Houyi stands on the first letter of HSBC, ancient myth-feet resting on logo black on red, under which throbs a mad rush of numbers and commerce and machines: trades riding cellular waves and fiber optic, fortunes made and shattered in minutes. She does not shade her eyes.

Nor does the author.

Scale-Bright is brilliant, if a bit beholden. You need to read it. But do yourselves a favour, folks: spend some time with the short fiction it springs from first.

Scale-Bright is available now from Immersion Press.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.